In our days, when both the pleasures and the troubles of the world constantly call us to depart from our Orthodox faith and morals, it is useful to us to recall the martyrs and confessors for the faith. Quite recently, less than 100 years ago, they would have consented to die rather than take such a step. One of these confessors of Christ was the Romanian elder Archimandrite Teofil (Bădoi; † July 17, 2010).

This article originally appeared in the Romanian journal “The World of Monks” (Lumea Monahilor), vol. 1, no. 1, July 2007.

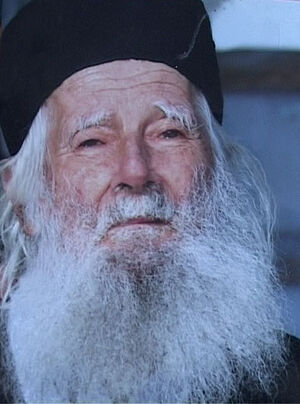

Archimandrite Teofil (Bădoi)I’m at the Monastery of Sâmbăta de Sus. Fr. Teofil (Pârâian), whom I came to see, was out for a bit, and I decided to take a walk to the lake, beyond the monastery enclosure. I saw a group of monks resting there. In the midst of them, as if being guarded by them all, stood an elderly monk, short of stature, with a thin, gray beard. Curious by nature and eager to talk, I went up to them:

Archimandrite Teofil (Bădoi)I’m at the Monastery of Sâmbăta de Sus. Fr. Teofil (Pârâian), whom I came to see, was out for a bit, and I decided to take a walk to the lake, beyond the monastery enclosure. I saw a group of monks resting there. In the midst of them, as if being guarded by them all, stood an elderly monk, short of stature, with a thin, gray beard. Curious by nature and eager to talk, I went up to them:

“God help you! Where are you from, fathers?”

“God help you! We’re from Slănic Monastery, from Argeș,” one of them, a young man, answered.

“I know someone there,” I said, “Fr. Teofil (Bădoi)!”

Suddenly the old man turned to me and said with all seriousness:

“Who?! That thief? That scoundrel? He ran away from the monastery. He’s not with us anymore!”

I looked at him with bewilderment and some fear. How could it be that this father, about whom I had learned many good things from books, had such a bad reputation in Slănic? The others were silent, hiding their smiles in their beards. Then one of them, seeing that I was completely perplexed, came over to me and happily said:

“Why, here he is—Fr. Teofil (Bădoi), the abbot of Slănic!”

Fr. Teofil (Bădoi) was born on September 11, 1925. He entered the monastery on February 20, 1944, and received the monastic tonsure on March 30, 1947. He was ordained as a hierodeacon on July 14 that same year. In 1968, having already gone through the school of suffering—seven years of exile from the monastery by the diabolical decree of 19591— he was ordained as a hieromonk.

A conversation with Elder Teofil

—Ah, my boy, youth is spent in temptations, and old age in infirmities. My voice has become weak; everything is weak. I’m left with one eye and one tooth. But what can you do? We have to go forward. That’s what Elder Vitimion used to say.

Even if I had graduated from all the schools of this world, even the highest schools, not a single one of them would have been as useful for me as the school of sufferings. I was driven out of the monastery on January 15, 1961. I was thirty-six. I stayed in Slănic with Elder Vitimion (Jupânu, as we called him) and Fr. Joseph from the village of Corbi. Fr. Nikodim and Fr. Gavriil were already in jail. I miraculously avoided prison. God kept me safe, otherwise I wouldn’t have made it. I simply would have died. That’s how it was.

I was preaching then in the “Lord’s Army.”2 I did it with great love. I was ready to bring all the young people to the monastery. Then, on October 14, 1960, comrade Bărbulescu, the inspector of religious affairs for the Argeș Province, the evilest man I have ever seen, came to the skete. He told me: “I came to meet you, because you’re the only monk in the whole province I don’t know—to meet you and tell you to leave.” “I’m not going anywhere, comrade. I’m not leaving here until spring.” “You’ll leave, I promise you.”

He turned out to be right. One night, Bărbulescu and three or four securists3 burst in. I had Fr. Bobok hidden in one of my rooms. He was sick, the poor man, and I was taking care of him.

“Where’s Bobok?” he asked. “What’s that to you, sir? Leave him alone. He’s sick.” They suddenly found him, and oh, what my ears heard… What filth, what abuse was spewed out upon him!

—Did they beat him?

—No, they didn’t beat him. They arrested him and kicked me out of the monastery. “Where are you going now?” the inspector asked. “To Corbi.” “And why not to Vlădeşti?”4 I didn’t want to return to my village, but they didn’t understand why I, being a monk, couldn’t return home. “I have no one to return to in Vlădeşti. My parents are dead.” Then they let me go to Corbi. They just made me sign a statement where I asked to be shot if they found me in the skete.

—How many years did you spend in forced settlement in Corbi?

—Five years, until November 1966.

—Did they leave you alone there?

—Of course not! They were constantly calling me in to the police. When I returned from there, I could barely stand on my feet. I was staggering worse than a drunk. “Bandit, why aren’t you married?” They always considered me a “bandit.”

“Listen, you! People like you get married but live separately from their wives. What do you say to that?” “I would say that those who are married must observe all the laws of marriage. I know this. And whoever isn’t married must observe all the laws of the celibate life.”

Another time, I asked the interrogator: “You also took an oath, in the military, didn’t you?” “Yes, I did.” “And so, have you broken it?” “No, never!” “And I have also taken an oath—monastic vows. And I can’t break them for anything in the world.” And do you know what he said? “You do well not to break them.” Can you imagine?

—So you kept your monastic vows even in the world, as a citizen.

—I kept them sacred, Father, with God’s help! I had temptations from the servants of satan. They were watching me, every step I took, and everything I did. And because of this stress, I couldn’t sleep at all for those five years I was living in Corbi, unless I took pills.

But satan also fought with me personally. If you could have seen what I looked like then, all skin and bones, you would have shed tears of pity. And the demon of lust took up arms against me, in this pitiful state of mine. I prayed so much, Father, that God would deliver me from it, that the tears I shed formed a puddle on the floor. Sister Veta asked me why I was crying, and I said I was crying out of longing for the monastery. I couldn’t tell her why.

And then I saw that the securists were worse than the demons. You could pray to God and be delivered from the demons, but from the securists… I would weep until I fell unconscious. Mother Gabriela later said: “If you only knew how many times I slapped you, your holiness!” “What do you mean?” “That was the only way I could revive you.”

***

Elder Teofil would say:

“When they ordained me, I prayed to God: ‘Lord, deliver me from envy and greed!’ They ruin good relations with people. I didn’t save any money and everything I did, I did for the monastery. I bought a lot of books—this is the legacy I leave to my ‘soldiers.’ I also have 700 cassettes with homilies, Church music, and recordings of various moments from my life.”

The elder would also say:

“The priesthood is the most terrible thing on Earth. When a priest is serving, he has Paradise on the right and hell on the left. A priest will give an answer for every soul from his parish, if any should perish. The priesthood is not a profession, but a Divine mission. My soul hurts when I see young people, future priests, going to study theology without thinking about what yoke they’re being harnessed to.”

***

When Fr. Teofil went shopping in Pitești with the monastery steward sometime after 1990, he was stopped by some citizen who proudly declared:

“Father, I’m an evangelist.”

The elder looked at him with surprise and responded:

“I only know four evangelists. And where did you come from?”

This unexpected response stunned the “evangelist.” Father had already walked a ways off, and the “evangelist” was still standing there, not moving from his spot. He wasn’t moving, as if rooted to the spot, following the elder with his eyes, until he disappeared into the crowd.

***

I often heard him say:

“Discos, sectarian houses of worship, and weekend markets are the mouth of hell. Whoever buys and sells on Sunday instead of going to the Divine Liturgy will reap no profit—only harm! This is what the holy fathers say, and I believe it’s true!”

***

Fr. Teofil also said:

“I have had many desires in life that I prayed to God about, for Him to fulfill them if they were pleasing to Him. I really wanted to build a church, because we’d be commemorated there both during life and after death, as long as the church exists. Wherever the Divine Liturgy is served daily, there many blessings are poured out from God. You know, the fathers of the Church say that that greatest good deed you can do in a day is to go to the Divine Liturgy. And I am filled with joy when I see three churches that have been erected and I see that the daily cycle of Divine services is being celebrated there according to the monastic order, with the Divine Liturgy.

“When I first went to the Holy Land, I saw how exalted and filled with peace the Divine services served at night were there. The holy fathers say that prayer at night is golden, because the mind is not so disturbed by thoughts as during the day.

“The scattering of the mind in prayer leads to the cooling of the soul, and the soul does not receive as much benefit as when the mind is gathered in prayer and we shed tears.

“Having returned from Jerusalem, I gathered my ‘soldiers’ to consult with them about how we could introduce nighttime services. So we started celebrating the Midnight Office and Matins at midnight. Since then, I have seen the blessing of God, for the community has grown in numbers, and also, I hope, spiritually and materially.”